Adria’s family businesses face their greatest challenge yet — passing the torch without losing their soul.

In the Adria region, the most delicate transfer of power isn’t happening in parliaments — it’s happening in kitchens, conference rooms, and board offices still bearing their founders’ names. The entrepreneurs who built fortunes through the turbulence of the 1990s are now confronting their final, most personal negotiation: letting go.

Their companies — industrial giants, consumer brands, hotel chains, distilleries — once stood as monuments of survival in post-transition economies. Today, they stand for something else: how to pass the reins without unravelling everything built by instinct, grit, and sheer will.

The Great Hand-Over

In Adria, the family name remains the ultimate business credential — and sometimes its biggest burden. More than two-thirds of the region’s private firms are family-controlled, yet few have written succession plans. Founders hover between pride and fear, torn between preserving a legacy and surrendering control. Their children, raised on Erasmus scholarships and global ambition, see leadership less as inheritance and more as responsibility.

In Croatia, Atlantic Grupa remains a rare model of continuity. Founder Emil Tedeschi has gradually drawn his sister, Lada Tedeschi Fiorio, into strategic leadership — a transition that feels less like succession and more like evolution.

As Group Vice President for Strategy and Development, she speaks the language of transformation, not inheritance. Her rise marks a generational shift in tone: the next wave of family leaders is proving that purpose can coexist with profit.

In Slovenia, companies such as Riko and JUB have found balance between family oversight and professional management. In Serbia, Tijana Škorić Tomić, co-founder and CEO of the family distillery behind Gorda Rakija, is doing something rarer: transforming an old craft into a contemporary brand.

Her version of succession isn’t about inheritance of assets but of vision — turning a family’s tradition of plum brandy into a design-driven product that speaks the language of modern luxury.

Across the region, one question lingers: can heritage survive innovation? “You can delegate authority,” a Belgrade industrialist says quietly, “but it’s hard to delegate identity.” The sentence hangs like a founder’s portrait still watching from the boardroom wall.

Two Heirs, Two Lessons

Modern Heirs, Modern Rules

If the first generation built from instinct, the second is building from intention. The heirs of Adria’s business dynasties talk less about market share and more about sustainability, transparency, and legacy. They’re introducing ESG metrics, hiring independent directors, and replacing hierarchy with collaboration.

Many have lived abroad, studied in Milan or London, and returned with a sense of duty that feels both global and local. They see companies not as private kingdoms but as shared platforms. “We inherited not just a company, but a story we have to rewrite,” says a young successor from Slovenia. “If we copy our parents, we fail them.”

In Croatia and Slovenia, heirs are launching venture arms to invest in start-ups. In Serbia and Montenegro, younger family members are transforming family-run production companies into export-ready brands. The goal is not to escape legacy — it’s to modernise it.

The family business, once defined by surnames, is becoming a test of imagination.

When Continuity Meets Complexity

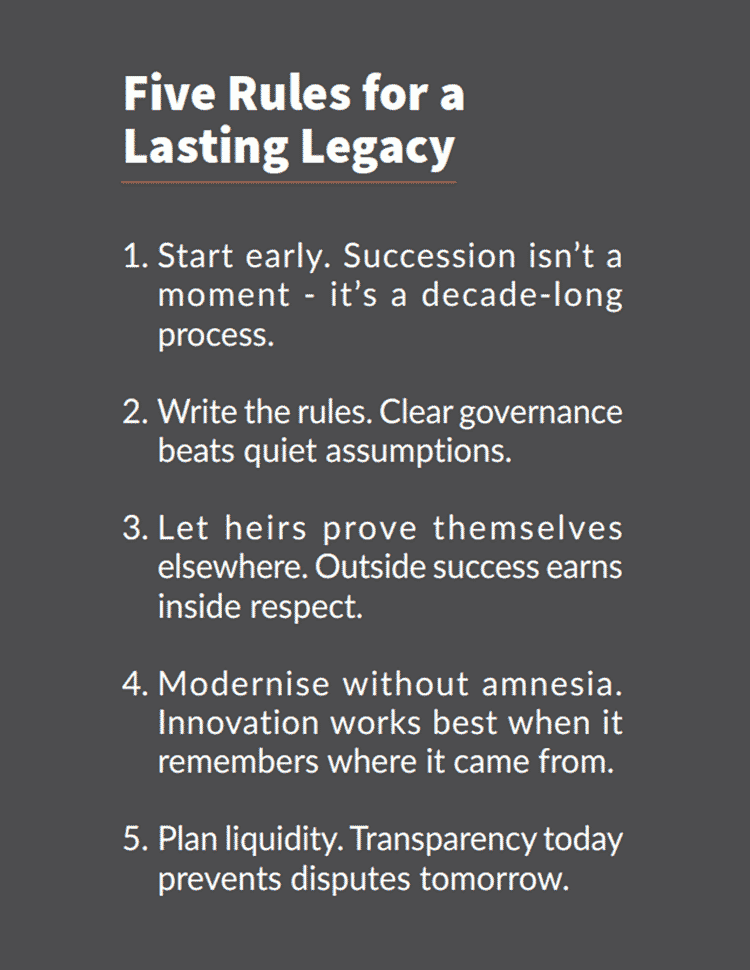

Smooth transitions are still the exception. Too many firms rely on founders’ personal networks, their charisma, or informal systems that vanish with them. Legal frameworks remain inconsistent across borders; inheritance processes are slow and often taxed twice. And the emotional dimension — the quiet struggle between pride, fear, and trust — is harder to quantify.

Letting go is an art few founders have time to master. Boards are often family gatherings disguised as governance. Heirs tread carefully, unwilling to overstep yet impatient to modernise. In many cases, transition comes not by design but by crisis.

Still, the region is evolving. Law firms now advise on family governance. Private banks offer succession planning.

Business schools in Ljubljana, Zagreb, and Belgrade teach intergenerational leadership as a discipline. Adria is learning to professionalise the art of staying in the family.

“Succession is no longer about bloodline,” notes a consultant. “It’s about mindset — the courage to keep what works and change what doesn’t.”

In other words, family business is becoming less about family — and more about business.

Legacy as Liability

Not every transition ends well. Across the region, family feuds, unclear ownership, and sudden leadership vacuums have frozen companies mid-evolution. In some cases, heirs sold off assets to avoid disputes; in others, founders refused to retire, stalling innovation.

A textile manufacturer in North Macedonia collapsed within a year of its founder’s passing — not because demand disappeared, but because two siblings couldn’t agree on who should sign supplier contracts. A coastal hotel group in Montenegro nearly met the same fate until foreign investors stepped in, replacing family board members with professionals and recapitalising the business. And a bakery chain in Serbia, once a symbol of post-transition entrepreneurship, split in two after cousins fought over expansion rights.

“Legacy can be an anchor or a shield,” says one regional banker who has financed both turnarounds and liquidations. “Sometimes it weighs more than it protects.”

The cautionary stories circulate quietly in boardrooms — whispered warnings to founders who still treat succession as a taboo. But they also serve another purpose: they make visible what Adria is learning the hard way — that continuity requires design, not destiny.

The Next Chapter of Family Capital

When it works, succession delivers something modern capitalism often forgets: continuity with conscience. Family firms think in decades, not quarters. They treat reputation as capital, employees as kin, and communities as silent shareholders.

Economists estimate that family-owned firms generate more than half of the region’s GDP and employ nearly two-thirds of its private workforce. Each successful handover secures stability; each failed one erases decades of knowledge and trust.

Globally, a similar handover is under way — from Italy’s industrial dynasties to Japan’s multi-century trading houses. Adria’s test is the same: can founders step aside before fate forces them to? And can their heirs preserve the founder’s fire without inheriting the burnout?

The next decade will reveal which family empires outgrow the cult of the founder to become lasting institutions. Those that do will shape a new chapter of regional growth — one defined not by survival, but by stewardship.